What do you get when you combine an erroneous belief about God, an ancient fable, an old theological heresy, and the lyrics to a favorite hymn? In this case, a Messenger Bible study with enough intrigue to fill two issues!

‘Bootstrapism’ or sound theology?

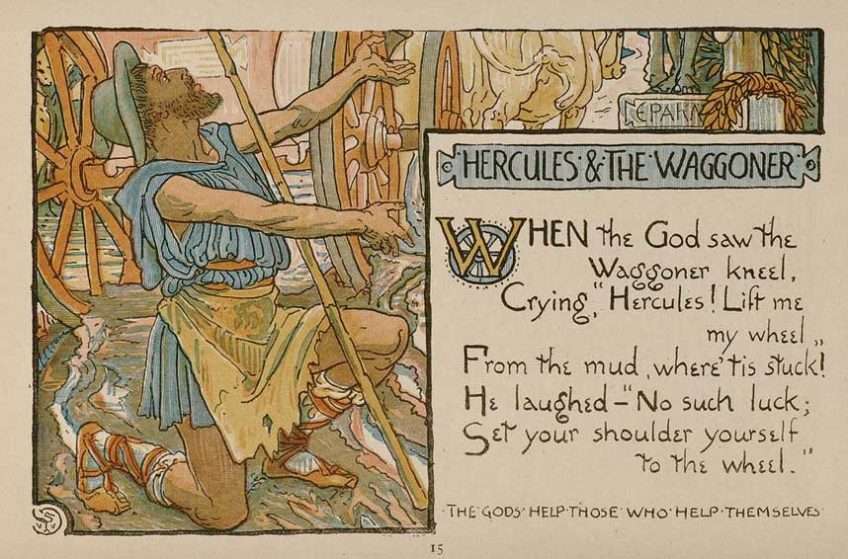

The saying “God helps those who help themselves” was made popular by its inclusion in a 1736 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac. It turns out, however, that the phrase is much older, first appearing in Aesop’s fable “Hercules and the Waggoner.” In this fable, a wagon is hopelessly stuck in the mud. Appealing to Hercules for assistance, the waggoner is told, “Get up and put your shoulder to the wheel. The gods help them that help themselves.”

With a background like this, how is it that people are inclined to believe this saying represents Christian doctrine? Perhaps it is because of our American cultural context, where we’ve been taught to pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps. Stories of the underdog succeeding through the sweat of the brow and good luck are always popular.

Do we really believe that God relates to us in this way? There are times when I am inclined to think that we do. Have you ever faced a particular disappointment and thought, “If I only had more faith, then God would have brought about a different outcome”? Or have you ever heard someone say, “The reason our church isn’t growing is because we’re not faithful enough”?

Statements like these come dangerously close to the idea that we earn God’s favor through our own behavior. The Bible, however, tells a different story. At heart, the issue concerns human nature and God’s grace: are people naturally good or bad? Romans 5:12-17 brings this question sharply into focus. But first, let’s consider some Christian history.

Church history and a popular heresy

Christianity was mostly a persecuted, minority faith until the fourth century when it became an official religion of the Roman Empire. The change in status helped attract affluent Roman citizens in large numbers for the first time. Suddenly, church leaders were wrestling with the nature of discipleship. Pelagius was a British monk who served Christians like these in Rome. While his name would eventually be given to two heretical viewpoints (Pelagianism and semi-Pelagianism), Pelagius believed quite strongly that people’s faith ought to show clearly in their behavior.

Pelagius also was concerned about the doctrine of total depravity, that people’s sinful nature leaves them unable to participate in their own salvation. This idea concerned Pelagius; if humans are hopelessly lost in sin, why would people in his congregation even bother trying to follow the ethical teachings of the New Testament? Pelagius concluded that God’s grace was abundant enough that humans could fulfill God’s commands without sinning. While he never said it quite this way, the implication was that God will help those who help themselves.

St. Augustine, the famous bishop of Hippo, strongly opposed these ideas. Augustine faithfully led the church of north Africa through times of intense persecution, including helping the church decide how to respond to Christians who abandoned their faith under threat of persecution but then wanted to rejoin the church when it became safer. Quite possibly because of his more difficult pastoral context, Augustine arrived at the conclusion that humans could do nothing on their own to fulfill God’s commands; all hope for salvation lies on God’s side of the relationship.

Augustine and Pelagius defended their own views—and attacked the other—through letters and sermons for several years. Ultimately, Augustine’s views were upheld by the Council of Carthage in 418. Pelagianism was declared to be heresy.

A challenging scripture

Romans 5:12-17 is one of Paul’s more theologically complex passages. One question to keep in mind when considering the text is this: do human beings need to be improved or do we need to be born anew?

Pelagius took the former view, understanding the phrase “all have sinned” in verse 12 to refer to individual sinful acts. Sins are acts that people choose to do, and that with a bit of care they could choose not to do. He concluded that if people could just stop sinning—or possibly never sin in the first place—then our own righteousness would assist God in our salvation. The ethical behavior the New Testament expects would be counted as faithful work on the human side of our relationship with God. People would, in effect, be “helping themselves,” making it possible for God to help us.

Augustine strongly disagreed, believing that people need to be born anew. Considering the broader context of Romans 5, Augustine noted Paul’s words in verse 15 that “the many died through the one man’s trespass.” All of humanity is guilty through Adam’s sin, but all persons have the possibility of being made new through “the grace of God and the free gift in the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ.” Commenting on this verse, Martyn Lloyd-Jones described human relationship with sin and grace in this way: “Look at yourself in Adam; though you had done nothing you were declared a sinner. Look at yourself in Christ; and see that, though you have done nothing, you are declared to be righteous.”

There’s more to come . . .

Understanding this popular little phrase has led us on quite a journey—and there’s still much to say, including how the Brethren have historically viewed sin, grace, and salvation. That will need to wait until next month. Between now and then, I invite you to consider these questions:

- I was raised to believe that people are basically good and, given the opportunity, will do the right thing. Larger societal issues such as racism, gun violence, and other assaults on human life cause me to question what I was taught. What do you think? Does your observation of human behavior lead you to believe that people simply need improvement (as Pelagius believed) or do we need to be born anew (as Augustine believed)?

- Take a look at the first verse of “Amazing Grace” in the Church of the Brethren hymnal published in 1951 and in the current hymnal published in 1992. The words are not the same. How do the different lyrics affect the meaning of the hymn?

- Romans: God’s Good News for the World by John Stott (InterVarsity Press, 1994)

- Doctrine: Systematic Theology, Vol. 2 by James W. McClendon Jr. (Baylor University Press, Second Edition, 2012)

- Christian Theology by Millard J. Erickson (Baker Academic, Third Edition, 2013)

Tim Harvey is pastor of Oak Grove Church of the Brethren in Roanoke, Va. He was moderator of the 2012 Annual Conference.