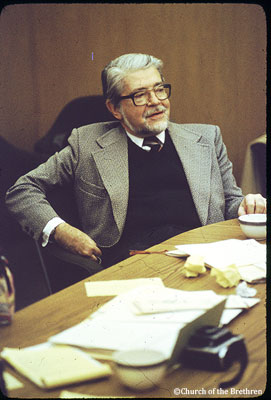

Photo by Church of the Brethren/Messenger

We know Kenneth I. Morse as the author of “Move in Our Midst,” the hymn that provides the theme for Annual Conference this year. But Morse also was a poet, author of worship resources, writer of Sunday school curriculum, and editor and associate editor of the denomination’s Messenger magazine for 28 years. During the turbulent 1960s, he wrote an editorial responding to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., lifting up King as a prophetic dreamer. Letters poured in of two kinds: either shocking expressions of racism, bigotry, and hatred, or very supportive of King’s work and thankful for Morse’s editorial. So that June, Morse wrote a follow-up editorial expressing his conviction of the Gospel call to care for the poor. It was titled, “A Little Careless about Mathematics.”

Following is the editorial from the Messenger of June 20, 1968. Read more about the life and ministry of Ken Morse in the June 2013 issue of Messenger, which features an article by former editor Howard Royer. For a Messenger subscription, which includes access to the digital edition, contact Diane Stroyeck at 800-323-8039 ext. 327 or messengersubscriptions@brethren.org. Cost is $17.50 annually for individuals, $14.50 for members of a church club or for gift subscriptions, or $1.25 per month for a student subscription.

A Little Careless about Mathematics

Jesus said the strangest things. His words were just about as unconventional as the things he did. Either he was impractical—apparently lacking in sound business judgment—or his standards were of a different order from those that prevailed in his time—and in ours also. Or maybe he was just a little careless about mathematics. At least he had a unique approach to arithmetic.

You know how it went with the stories he told. Like the case of the shepherd who had ninety-nine sheep safely in tow—but, not satisfied with such a high margin of achievement, he risked everything to go looking for the one that was lost. And Jesus, in telling the story, seemed to lose all sense of proportion, for he argued that there would be more joy in heaven over one lost sheep, one sinner who repented, than over ninety-nine who did not need to repent.

But the most puzzling of all his parables is the one in which Jesus propounded some odd ideas about wages and hours of working. A householder went out early one morning to round up workers for his vineyard. The rate of pay was about twenty cents. But he needed additional help and therefore he hired others as the day went on—at the third hour, the sixth hour, the ninth hour, even at the eleventh hour, some of the unemployed were signed up. At the end of the day, each worker received his twenty cents, the eleventh hour employee as well as the early riser. Naturally the fellows who put in longer hours were unhappy; but the householder insisted that he had kept his bargain. If he wanted to treat the last as well as the first, what was that to them?

Today, as in the time of Jesus, our communities are filled with scribes and Pharisees who insist that because they have worked hard, because they have managed well, and especially because they maintain law and order, their prosperity is a sign of their special merits and they should not be expected to go out of their way to give any aid to eleventh-hour laborers who are a little less prompt, a little less energetic, or who may have suffered because of special handicaps due to their race, their color, their religion, or their language. The contemporary Pharisees have made it quite clear that the poor are poor only because they will not work, that no one need live in a ghetto if he is willing to move out of it, and that all this talk about helping segments of our society on the basis of human need is just so much socialistic nonsense.

To them it comes as something of a shock to hear Jesus insist that the rewards of God’s kingdom are not to be distributed on the basis of a man’s merit but rather on the basis of God’s grace. According to Jesus, God is the kind of employer who cares little about arithmetic but cares tremendously about people, including the poor people who make their visit to Washington at the eleventh hour. The oil prospectors, the farmers, the doctors, the corporation representatives, the military professionals, the plantation owners—all of these and many others have been busily at work in the federal vineyard, asking for write-offs, no-risk contracts; lobbying for legislation that would benefit them; and working to defeat laws that might restrict them. Yet now they have become righteously indignant because a few thousand poor people have come at the eleventh hour to ask for a chance to earn their twenty cents.

The gospel that Jesus proclaimed contains good news for the poor—and for all others who cannot qualify for the merit badges that are supposed to guarantee them a place in the sun. The disturbing thing about Jesus’ teaching is that he is so generous in extending God’s grace and forgiveness to the undeserving—the harlots, the misfits, the failures, the dispossessed, the hungry, the lame, the blind, the diseased, the broken, the alienated. The amazing thing about God’s grace is that it forgets about merits and emphasizes instead the spendthrift nature of divine love. God is not a stern accountant keeping books of every man’s indebtedness but a loving Father who is concerned about individuals of every shape and size, of every custom and color, of every race and nation.

Messenger hears frequently from readers who say, “You talk about race and war and poverty and neglect to preach the gospel.” For the record, here is an editorial about the good news of the gospel of the grace of God—a grace so marvelous that it puts Jesus on the side of the poor, a love so forgiving that it cannot tolerate war-making, and a gospel so universal that it binds man to man (all races included) as well as man to God. K.M.