It’s cheaper to educate Indians than to kill them.” These were the words of Indian Commissioner Thomas Morgan when he spoke at the establishment of the Phoenix Indian School in 1891.

The Phoenix Indian School in Arizona was one of many Native American boarding schools born out of a federal policy of assimilation, and the Church of the Brethren has a surprising, little-known history with the school.

Boarding schools were operated by the US government— and churches working with the government—from about 1860 to 1978. Tribes had already been violently removed to reservations that were a fraction of their homelands, and now Native American children were forcibly removed from their homes once more. They were taken from their families and placed in schools far from their tribes, far from their culture, far from everything they knew.

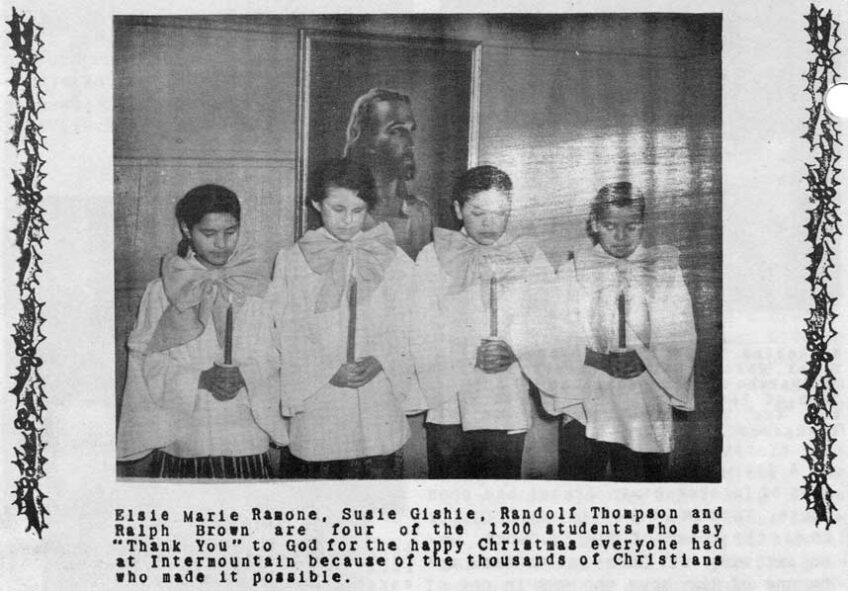

Fast forward over 50 years from the time those chilling words were spoken, and Brethren Volunteer Service (BVS) workers were being sent to serve at that very school in Phoenix and at Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah. How did we end up contributing a piece, albeit small, to this messy history that makes up our relationship with the people indigenous to this land? How do we grapple with that past?

It’s a complex story, but it’s well worth reckoning with if we ever hope to live in right relationship with those who our country has done so much to harm.

“Home’s the place we head for in our sleep,” writes Louise Erdrich in her poem “Indian Boarding School: The Runaways.”

“Boxcars stumbling north in dreams

don’t wait for us. We catch them on the run.”

Erdrich tells the common story of painful homesickness felt by many children at the schools, prompting kids to run away, again and again, seeking to make it back to their homes.

“We know the sheriff’s waiting at midrun

to take us back. His car is dumb and warm.

The highway doesn’t rock, it only hums

like a wing of long insults. The worn-down welts

of ancient punishments lead back and forth.”

This is the experience of so many children for decades, aching for home, and, all the while, slowly losing parts of themselves that tied them to the very places they missed. During the late 1800s and early 1900s, boarding schools were barely even educating Native children. Many were industrial schools, which taught a trade, forced students to work for cheap labor, and kept a strict militarized environment.

In the 1930s, following the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, boarding schools slowly moved toward a greater focus on education. However, as Arizona Central’s podcast Valley 101 notes, the goal was the same—remove all Native identity for generations of tribal members and therefore remove everything that gives them claim to their land in the first place. It was both a social tool steeped in racism and an economic tool to access land.

This is where churches come in. Many boarding schools were begun by historically white church denominations seeking to civilize and convert Native peoples. Despite the fact that tribes, for hundreds of years, had lived in cities, developed complex agricultural systems, and possessed rich religious lives, the story since European colonization said that tribes were backwards, savage, and uncivilized. These diverse Native nations didn’t fit into a European understanding of “civilization,” so the depth and intricacy of the cultures were lost on American society for generations.

Churches were acting based on these same incorrect ideas about Native peoples, which meant that students at boarding schools were taught that their indigenous cultures and religions made them heathens, and that they must reject their sacred practices in order to be viewed as equivalent to white people. Their hair (a deeply sacred symbol in many tribes) was cut, their clothing was replaced, and they were banned from speaking their native languages and practicing their cultures. In the earlier years, punishment for breaking these rules was harsh and physical. Many Native scholars and activists define this as a cultural genocide—in other words, these were efforts to obliterate tribal cultures in order to wipe out Indigenous communities from the US.

As the years continued, schools generally had fewer harsh punishments and cruel instructors. The removal of culture continued, but was masked by good intentions and a true desire to move members of tribes into the American cultural mainstream, regardless of whether they wanted to. The 1960s saw another shift—the establishment of Native-run schools within tribes. Throughout the decades following, government- and church-run boarding schools began to close, transfer to tribal ownership, or be repurposed.

The Church of the Brethren did not have any boarding schools of its own, but the historical record shows that this was likely not due to discomfort with the practice of assimilation. Regardless, the church, out of genuine concern in response to stories of poverty-stricken tribes, sought to work with Native Americans through connections with the National Council of Churches. The Church of the Brethren placed BVSers at Native American boarding schools and community centers, beginning with the Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah, and later including the Phoenix Indian School in Arizona. BVSers taught students in courses dedicated to religious education.

Two members of the Hopi nation who graduated from Phoenix Indian School in 1959 recounted their experience in the Valley 101 podcast episode. Leon and Evangeline mostly recall positive experiences from attending school in the 1950s, closer to the end of the boarding school era and after the tactics of the schools had shifted somewhat. Overall, the two remember their instructors being caring and kind, and there is a high chance that BVSers who assisted with religious education classes were some of those very instructors.

However, as Evangeline tells her story, she remembers attempting to run away, so overcome by homesickness from missing their ceremonies that she risked the punishment in return. Through tears, she also tells of the trauma of being at school in times of grief: “I lost my grandma when I was a senior in high school, and nobody told me.”

In 1957, one of the BVSers at the Phoenix Indian School wrote in the Gospel Messenger about her work: “Many of the students have had little or no religious instruction before attending school. Some tribal religions are strange and hard to penetrate. Sue Begay and Johnny Blueyes will need much religious instruction to stick with them whether they choose to return to the reservation after school or go to the white working world following graduation. Here we have this opportunity, because at school we can place Christianity and religious instruction into their curriculum. The adjustments they must make are many. Usually they change quickly from bright beads, feathers, and tribal dress to the typical ‘paleface’ attire, or from long stringy hair to crew cuts and well-curled shiny black hair, or from fried bread and beans to meat and potatoes, from hogans, tepees, and cliff dwellings to dormitories.”

This dismissiveness of the students’ own religious beliefs and their culture—clothing, hair, food—is a window into white America’s understanding of Native cultures at the time and, for many, still the understanding today.

Edna Phillips Sutton—the passionate woman who seemingly almost singlehandedly pushed the Church of the Brethren into working with Native peoples, giving land to the denomination for Lybrook Mission in Navajo Nation— wrote a number of articles in the Gospel Messenger in 1952 on the subject of Native Americans. One article, “The American Indian Today,” includes lines that call out how white Brethren have benefited from injustice: “We have lived and grown rich on the lands which our forefathers wrested from the Indians.” Yet, in another article, “Slums in the Desert,” she diminishes the sacred religions of those same people, saying, “Above all, they need to be freed from the fears and superstitions that torment and sadden their lives. They need Christianity.” Though this was rooted in true Christian desire to share the good news of our faith, this was also the very ideology used to create the trauma of boarding schools.

This is the dichotomy at the heart of the Brethren work with Native peoples in the mid-20th century: Brethren, ever eager to serve populations in need, stepped up to the challenge of addressing issues of poverty and injustice for oppressed peoples; at the same time, Brethren internalized many of the stereotypes and assumptions suggesting that white culture was inherently more evolved than the cultures of tribes and, through their work, perpetuated and spread those ideas.

We can, at once, recognize that we as Brethren were doing exactly what we thought was best and also recognize that we participated in a broader, deeply troubling part of American history.

Sometimes, unearthing pieces of our history means taking a hard look at our narratives, made fresh by brave people telling stories in recent years. The remarkable thing is that, despite a government-run project of cultural genocide, hundreds and hundreds of tribes in the US still retain many of their cultural practices and religions today and have rich revitalization efforts at work. This is a story of pain, heartache, and abuse, but it is also a story of resilience and hope.

It is a sacred thing to look back at such a history and speak truth. This is our task today and every day.

Monica McFadden recently served as racial justice associate in the Office of Peacebuilding and Policy. A year ago, she led a month-long Native American Challenge for the Church of the Brethren.